|

| Michael Douglas as Gordon Gekko in ‘Wall Street’ (1987) |

In late 1987, Frank Partnoy, then a maths student at the University of Kansas, had an epiphany. As he sat in a cinema watching Wall Street, Oliver Stone’s depiction of the corrosive effects of greed on the financial industry, Partnoy decided he wanted to be part of it.

“I was naive but it actually inspired me. It made Wall Street seem exotic and alluring,” says Partnoy, 43, who went on to work for Credit Suisse First Boston and Morgan Stanley as a derivatives specialist, an experience he chronicled in his 1997 book Fiasco: Blood in the Water on Wall Street. Now a professor of law and finance at the University of San Diego, he says: “If you are a math major at the University of Kansas and you see a cheque with six zeroes, it is going to get your attention.”

He was not alone. In the two decades since its release, Wall Street and its lead characters, the father-of-all-evil Gordon Gekko (Michael Douglas in an Oscar-winning turn) and the corruptible ingénu Bud Fox (Charlie Sheen), have exuded an almost hypnotic attraction on scores of would-be bankers and traders.

“[The movie] became a cult phenomenon on business school campuses,” says Ken Moelis, 52, a former UBS banker who now runs his own advisory boutique and is one of Wall Street’s best-known dealmakers. “[After they joined the industry] these kids told me that they watched it so many times I thought they knew more about Gordon Gekko than their families.”

A full 23 years after its premiere, most of the 20-plus real Wall Street denizens interviewed for this article displayed an encyclopaedic knowledge of the plot; Gekko’s ruthless attempt to raid an airline, aided by Fox’s inside tips until the young protégé’s conscience launches a successful takeover of his soul and both get their comeuppance. The real Wall Street, however, appeared to embrace Fox’s rags-to-riches social climbing while overlooking the story’s moral underpinnings. Not quite the reaction that Stone, the son of a stockbroker but known for polemical, political films such as Platoon and JFK, intended when he conceived a tale of the dangers of unbridled capitalism.

The film, however, took on a life of its own, defining a financial era in the eyes of the public and the industry it portrayed. Despite being neither a big box office nor critical hit, its influence on popular culture remains strong. Gekko-esque wisdom, such as “lunch is for wimps” and “greed is good” (the actual quote is “greed, for lack of a better word, is good”), has long since passed into common currency.

Indeed, many of those buying tickets for the sequel, Wall Street: Money Never Sleeps, released next month, will be alumni of the first film: the crowds lining up at this week’s New York premiere were made up largely of middle-aged men in suits pressed against barricades typically reserved for screaming teenagers.

For the inhabitants of the Street, the film’s impact went deeper and further than a collection of terse one-liners. “[Wall Street] inspired generations of financial people to ape the characters,” recalls a senior banker who joined the industry at that time. “All of a sudden, on trading floors there was a proliferation of suspenders [braces], slicked-back hair and Sun Tzu’s The Art of War [Gekko’s favourite book].

Although modern-day mobile phones are smaller than Gekko’s brick-like late-1980s contraption, visitors to old-school haunts such as the 21 Club in midtown Manhattan can still bump into crinkly gentlemen with gummed-up hair and braces – a bizarre case of life imitating art imitating life (Gekko’s look was itself inspired by that of 1980s financiers such as Carl Icahn and T Boone Pickens).

Wall Street was both a mirror and a high-water mark for the financial industry of the period. It chronicled the dramatic change that daring corporate raiders and the availability of cheap debt had introduced into a world of gentlemen’s agreements and handshakes in a cosy, old-boys’ network. Stone’s shorthand for that fading culture is the character of Lou Mannheim, the ageing stockbroker named after Stone’s father Louis, whose moralising – “Man looks in the abyss, there’s nothing staring back at him. At that moment, man finds his character. And that is what keeps him out of the abyss” – proves a bland counterpoint to Gekko’s more watchable moral turpitude.

Jean-Yves Fillion, 51, a banker at BNP Paribas in New York, says: “The movie was a reflection of the industry as it was at the time but it also captured a turning point. Finance used to be about stability, values and about relationships. The movie was at the opposite end of the spectrum. It showed a different side of finance that was taking hold.”

Fillion, a self-confessed film buff, compares the original Wall Street to a “modern-day western, with a bad guy that was almost likeable – a good bad guy. That made the whole industry more attractive, more shiny and glamorous. Gordon Gekko is portrayed as an example of sophistication and innovation, he is almost seen as a hero”.

. . .

|

| Gordon Gekko shows Bud Fox the money |

“I remember being surprised that a group of people was just figuring out that greed played a meaningful role in the way the business gets done on Wall Street,” he recalls. “I think the movie would have made a much more powerful point had the creators been a little bit subtler and cast the character not as a criminal but as ethically challenged, and styled him on those corporate raiders of the 1980s who took a tough, uncompromising stance against companies but did not actually break any laws.”

Yet the culture of greed that was obvious to a then 25-year-old banker such as Winters was still a surprise to most of the film’s non-Wall Street audience, partly because of the finance industry’s relatively low profile at that time among the wider public. Its release, just a few months after the stock market crash of October 1987, provided a timely account of an era of excess and revealed the ugly side of a money-making machine that has always tried to cover up its blemishes with fancy clothes and complex jargon. For the first time people were able to see not only the glory but the gory side of Wall Street.

Pat Huddleston, 48, a former official at the Securities and Exchange Commission (SEC), recalls how the movie played a part in his decision to become a regulator. “The way Oliver Stone wound up the story, with Bud seeing the light and embracing the values of his upbringing, reminded me that ordinary folks are the ones who suffer for the sins of the supposed kings of the universe represented by Gekko,” says Huddleston, who now runs Investor’s Watchdog, a private investor-protection firm that investigates suspected Ponzi schemes. “Given that I was following an impulse to work for David rather than Goliath, Wall Street helped me see that I could do that at the SEC. What I saw at the SEC, in the dark corners of the securities industry, confirmed the less than flattering portrait that the movie paints.”

Of course, others viewed it differently, seeing in this muscular, vivid portrait of money and its transformative social powers a modern parable for the American dream with braces replacing bootstraps. On Wall Street, as Gekko says to Bud, “If you are not on the inside, you are on the outside.”

Todd Thomson, 49, started his career as a management consultant before later joining the finance industry and for a period becoming an executive at Citigroup. He recalls how some of his classmates at Wharton Business School reacted to the film. “Wharton was my first exposure to people from Wall Street and people who wanted to go to Wall Street – and the focus was almost exclusively on making money,” says Thomson, who now runs his own investment fund. “A lot of people at Wharton came from nothing, a lot of them had backgrounds similar to Bud Fox. For them the life of Bud Fox was what they were aiming for: the dream of going from nothing and ending up with the penthouse apartment and a girlfriend with model looks.”

. . .

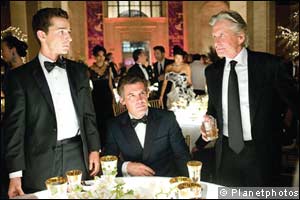

|

| Shia LaBeouf, Josh Brolin and Douglas in the sequel ‘Money Never Sleeps’ (2010) |

Just as the first film was inspired by the famous insider trading scandal involving the real-life arbitrageur Ivan Boesky (who reportedly once said “greed is healthy”), Money Never Sleeps borrows liberally from contemporary events. A common parlour game among bankers who have seen previews is to speculate on which real-life Wall Street titans have influenced the character of the vulture-like executive Bretton James, played by Josh Brolin.

The film also reprises the relationship between Gekko and a young protégé. Shia LaBeouf plays a trader who falls for his master’s fraud (clearly he hasn’t seen the original movie) while romancing Gekko’s daughter.

But it is not just the size of Gekko’s mobile phone that has shrunk since 1987. With the free market shown to be a lot less perfect than late-1980s zealots such as Ronald Reagan, Margaret Thatcher and Gordon Gekko had us believe, the reputation and social standing of bankers has also been cut down to size.

Stone’s cautionary precepts may, therefore, stand a greater chance of being heeded this time round. But can his new film hope to achieve anything approaching the resonance of the original? Those longing for memorable lines will not be disappointed. (“I once said, ‘Greed is good.’ Now it seems it’s legal;” “You are so Wall Street you make me sick. I am going to take a shower.”) But Partnoy, the banker-turned-professor, believes modern viewers will be less wide-eyed than those of his generation.

“The maths major at the University of Kansas now knows all about collateralised debt obligations and Wall Street,” he says. “When I show the original movie in class, the ethics of the students have changed 180 degrees. In the 1990s, it was seen as inspiring, today students get the morality tale right away,” he says.

The spotlight thrown on unglitzy parts of high finance has reduced Wall Street’s mystique. Forget swashbuckling corporate raids and daring trading strategies, the latest turmoil was caused by poor people who were given mortgages they could not pay and the nerds who securitised them in windowless offices. As Gekko languished in jail, Wall Street was taken over by lunch-eating wimps.

Paradoxically, as the “quants” elbowed the dealmakers aside, and super-fast computers replaced human beings on the trading floors, this less colourful industry became better known to the public. A period of long prosperity encouraged more people to dabble in investments.

Try as he might, Stone cannot shock many people the way he did two decades ago because his audience is both more knowledgeable about, and more inured to, the perils of finance.

Will the new film’s depiction of Wall Street’s current, more workmanlike, incarnation still exercise a gravitational pull on would-be traders? Bill Winters believes it will. “The-greed-is-good movement of the 1980s and 1990s carries on today,” he says. “Finance has always been a dog-eat-dog profession where some people became fabulously wealthy and some people get fired. There are a lot of bright kids that studied engineering and maths who want to go into finance because of the promise of great riches.”

Wall Street veteran Peter Solomon, 72, who was an executive at Lehman Brothers before founding his own firm in 1989, is unconvinced that a more penitent Gekko will increase his industry’s ability to learn from past mistakes.

“You go to a dinner party today and two or three of the guys who are there were in jail,” says Solomon, who met Stone before he began shooting the new movie. “It’s a great world because it’s so redeeming ... but I don’t think people learn lessons.”

Which is why the most prescient line in the 1987 film is perhaps not “greed is good” but the warning offered by Mannheim to the young Fox: “The main thing about money, Bud: it makes you do things you don’t want to do”.

No comments:

Post a Comment